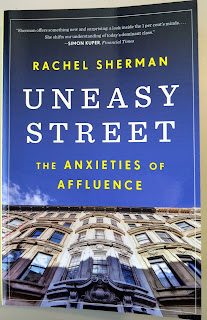

本書是社會學的學術專書(Princeton University Press, 2017),探問的研究問題是,財富金字塔頂端的富裕階層,如何自覺並回應自身的地位優勢。

作者Rachel Sherman是紐約著名的大學New School的社會學家。據作者自述,自己也來自優勢家庭。研究材料來自訪談。作者訪談55位富裕人士,另外也訪談30位為頂層人士服務的中間人(包括設計師、建築師、財務顧問、運動教練、廚師等)。研究場域是美國紐約市,是美國貧富差距最大的地區之一。研究進行的期間,紐約曾經歷「佔領華爾街」社運動。由於主題敏感,研究過程並不順利,拒訪率很高。研究者指出,她的受訪對象具有一定程度的偏差性。

本書的主要結論是,檢視不平等,重點應放在製造社會不平等的社會結構與社會過程,而不應放在個人的人格態度或行為。她強調,不論對於那個社會階層,都應該要避免個人化的歸因與道德評價,否則不僅無法弭平對立,反將複製不平等,成為繼續鞏固社會不平等的機制。

本書最後一節描述研究方法,包括研究過程與研究限制。書末並列出10個討論題目,適合作為研究設計與推論的參考。台大圖書館有電子書,我自己買了實體書。以下摘錄本書內容。

A Nutshell

Study participants

ü The author herself was raised in a privileged background and lived in NYC. She targeted people living in NYC, with high income and/or wealth (top 5% according to statistics), in their 30s and 40s, and had children. The author thought these people would likely make important lifestyle decisions such as buying houses, doing a renovation, choosing schools for their children, etc. (p14).

ü Snowballing sample was used, but the non-responding rate was high. It turned out that finding people who had recently done a major renovation on a house or apartment was an effective way to find these people (p17, p243) because home renovation is very common in NYC, and people enjoy talking about it.

ü A total of 55 parents were interviewed. Their income ranged from 250,000 to 10,000,000 (most of them above 500,000, or 年收入>1,500萬台幣) and assets ranged from 80,000 to 50,000,000 (most above 3,000,000, or資產>9千萬台幣). Among them, 80% were white, 20% were gays, all of them were college-educated and nearly exclusively in elite institutes, and 66% had advanced graduate degrees. They shared three characteristics: they had high levels of cultural capital, were politically liberal, and 50% were raised Christian; 33% were raised Jewish, but most were not religious (15).

ü Besides, the author interviewed 30 “intermediaries”, including financial advisors, coaches, designers, architects, personal chefs, etc.

Questions asked in interviews

1. Money and lifestyle issues – how do they spend? Do they compete for status or distinction?

2. Inner conflicts and moral concerns – how do they perceive their ‘privilege’? Whom do they compare with (upward or downward)? Do they think they are worthy of this privilege, i.e., the legitimacy and moral worth issues?

Content of Each Chapter

Chapter 1: Orientation to others.

Her research question is: how do rich people locate themselves on a distributive continuum? How did such self-location affect their perceived privilege and political standing? She distinguishes three types of orientation.

(1) People who looked upward from the “middle”: they were mostly in finance, business, real estate, or corporate law fields; more conservative; against tax increase; tended to socialize with people with similar wealth; compare upwards (p32); more economically insecure; having anxieties around privilege but reluctant to talk about it; hate to talk about “inequality”; annoyed by Obama's remarks because he talked about economic inequalities and criticized the “Wall Street people”, treating them like evils (p 43).

(2) People who looked downward: many were in creative or intellectual jobs; having more diverse social networks; more liberal; more open about their privilege; see and were concerned about people with less; having class-related discomforts and inner conflicts; many expressed affinity with the “Occupy Wall Street”; these people tend to think that all groups were connected with each other by economic relations and moral obligations; many of them believed that structural change is necessary and possible (p52)

(3) People with flexible orientations: A mixture. Classifying people into clear-cut categories is difficult because people are complicated, and attitudes are fluid and affected by many factors.

Chapter 2: Working hard or hardly working?

n Having a strong working ethic; it is “hard work” that make them feel morally worthy; strong opposition to ‘dependency on the state’

n Many admitted that they were lucky.

n hate to talk about “structure”

n sense of economic insecurity is high – fear of job loss, disease and health care cost, financial turmoil, etc.

Chapter 3: A Very Expensive Ordinary Life

n In short, her interviewees emphasized the “ordinariness of their expenses”.

Chapter 4: Giving back (time and money)

n Traditional public philanthropy and volunteerism were taken for granted as a part of their identity as good people, i.e., philanthropic identity.

n Paying tax was considered as giving back, but some interviewees were reluctant to accept tax rise; regardless their orientation and political stands, most people took advantage of rule holes to reduce taxes.

n Giving back, but not giving up, i.e., not challenging structural inequalities.

Chapter 5: Labor, spending, and entitlement in couples

n This chapter is about gender issues at home within wealthy couples.

Chapter 6: Parenting privilege – constraint, exposure, and entitlement

n This chapter is about how they raise and discipline their children.

Conclusion

The author pointed out that many arguments and comments, such as the Occupy Movement, the Fight for Fifteen (i.e., a policy agenda aiming to raise the minimum wage to 15 USD per hour), Sanders' 2016 presidential campaign, and Obama’s remarks on high-wage tax cuts, involved personal attacks. In her view, these remarks are counter-productive.

She reiterated that we should stop distinguishing good rich and bad rich and stop making personal judgments on their personal characteristics. Instead, we should engage questions about a more egalitarian distribution of material and experiential resources (p236). She reminded us that we should criticize the society and systems that produce unequal distributions of wealth and not individuals in the structure. Efforts should be made to promote “egalitarian thinking” (p236), to raise questions about “distributional justice”, and to challenge the commonly-held notion that people deserve resources merely based on individual moral status (p237).